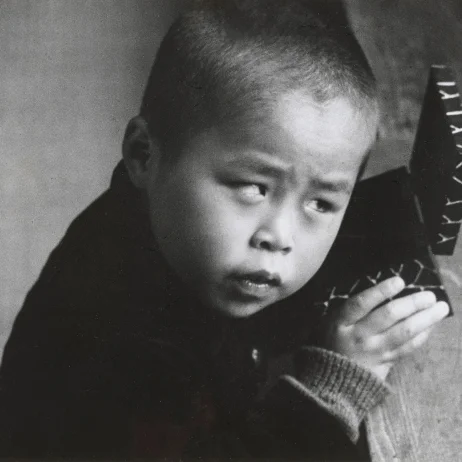

Ken

Domon

“I love beautiful things, and I want to

ind“A truly good photograph captures more than the naked eye.” — Ken Domon

“I love beautiful things, and I want to

indIn the current age anyone and everyone can make a name of themselves simply by taking photos on a device in their pocket and posting it on a social network, but what does it mean to be a truly great photographer? Using the right filter? Simply achieving the perfect balance of light and color? Or something deeper, something much more complicated than what our modern devices can provide?

“I love beautiful things, and I want to

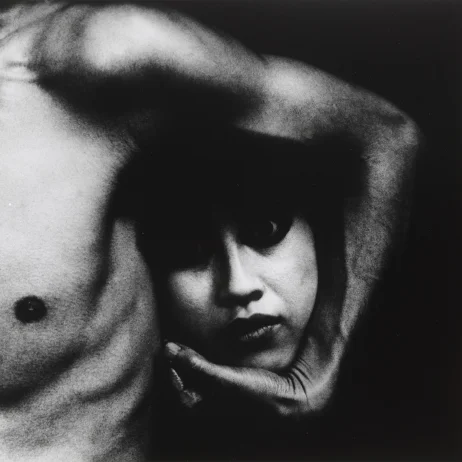

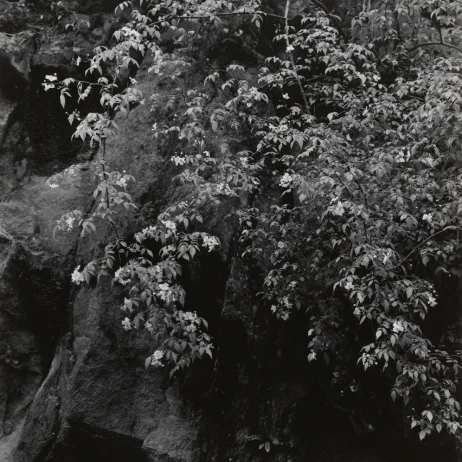

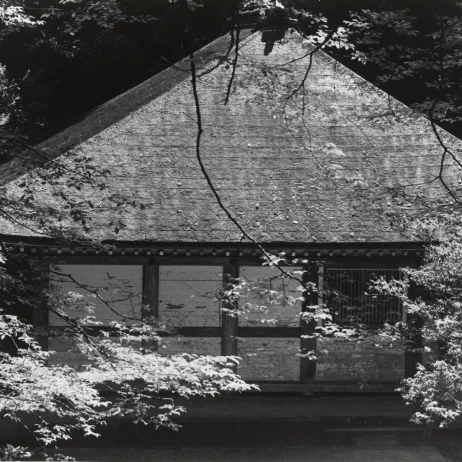

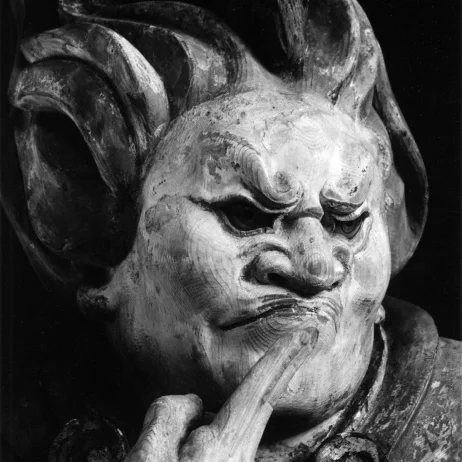

indFor Ken Domon, a truly good photograph is one that surpasses what the naked eye can see, it is “one that shows a side of an object that can only be seen in a photograph.” Domon spent many hours researching his subjects to learn everything he could about them. He once even spent one month in Muroji temple waiting for the perfect shot despite being ill.

Kubota has proved to be a remarkably

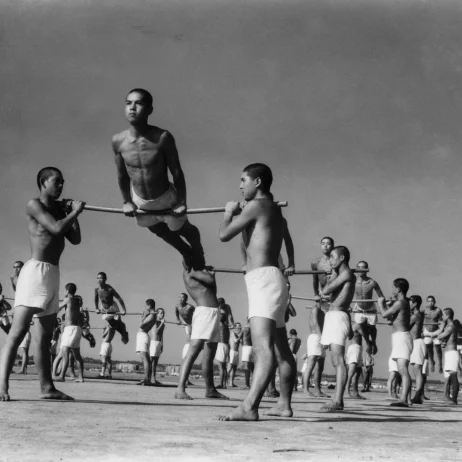

indIn 1935 Domon joined Nippon Kobo, an influential publishing agency that produced ‘Nippon’, a magazine aimed at introducing Japan to the West. Nippon Kobo was established in 1933 by Yonosuke Natori, who used innovative photography techniques learned during his time in Germany. There Domon oversaw photography for internationally-bound brochures, and he spent time in the Izu Peninsula working as a cameraman for Rintaro Takeda. The photographs taken during this time became the basis for Fubo, his first book on photography.

Kubota has proved to be a remarkably

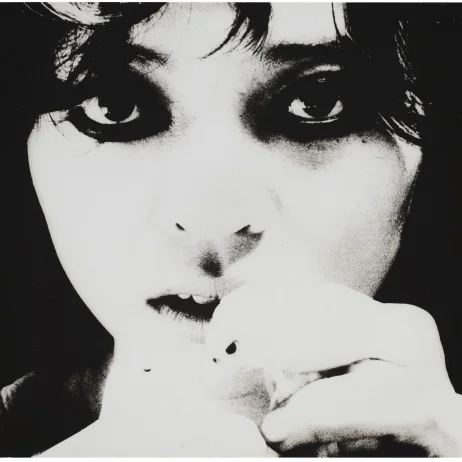

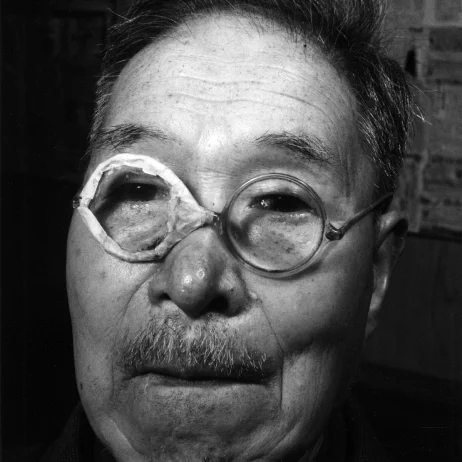

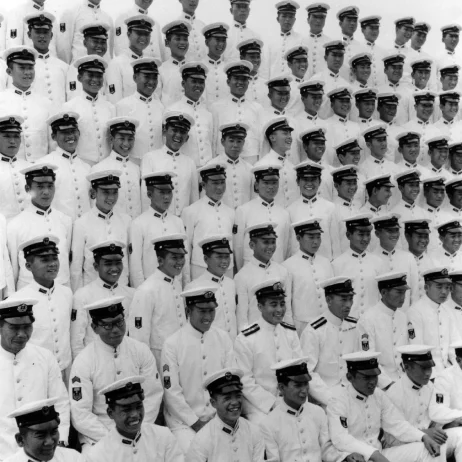

indDuring World War II, Japan lurched into disastrous militarism and became mired in a bloody war in China. Despite the encroaching crisis, Domon continued to produce critically successful work, gradually developing a reputation through a series of portraits that appeared in Shashin Bunka magazine and documentary photographs, winning the first Ars Photo Award in 1943 for a collection of his portraits.

Kubota has proved to be a remarkably

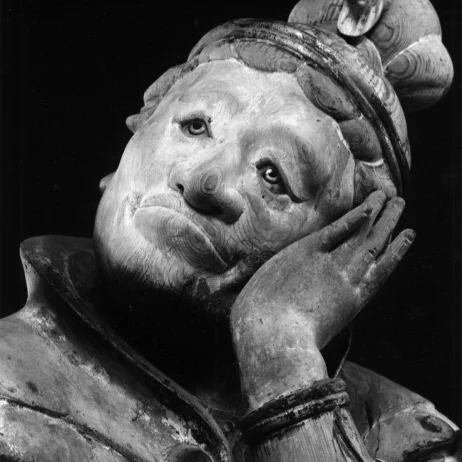

indAs the war intensified, Domon’s work as a photojournalist inevitably came under stricter controls. During this period, Domon concentrated on photographing the bunraku puppet theater, and started to take photographs at the temple Murōji in Nara Prefecture.

In 1965 Kubota left Japan for New York.

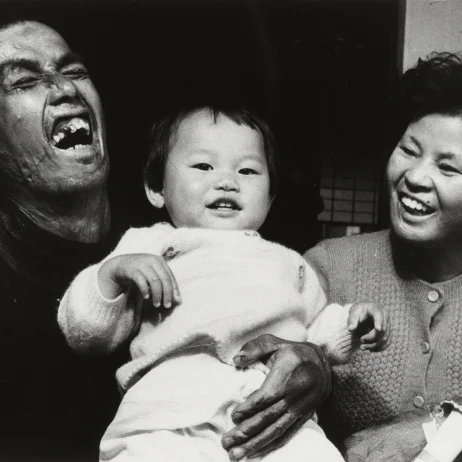

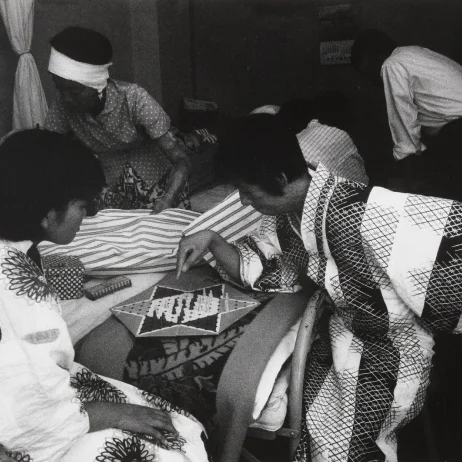

indOn August 15, 1945, the long war finally ended—and with it, Domon’s period of patient subservience. He launched himself on a series of ambitious and energetic projects, driven to find a way to use photography to respond to the turbulent social changes of the postwar period.

In 1965 Kubota left Japan for New York.

indFrom January 1950, Domon served as judge on the readers’ submissions page for the photo magazine Kamera. “All my faith, experience, and sincerity I dedicate to the cause of helping to establish photography socially and culturally as an independent form of modern art,” he stated, and true to his word, Domon threw himself into the work of appraising the submissions in each issue, writing long critiques to encourage and enlighten the readers who had sent in examples of their work.

In 1965 Kubota left Japan for New York.

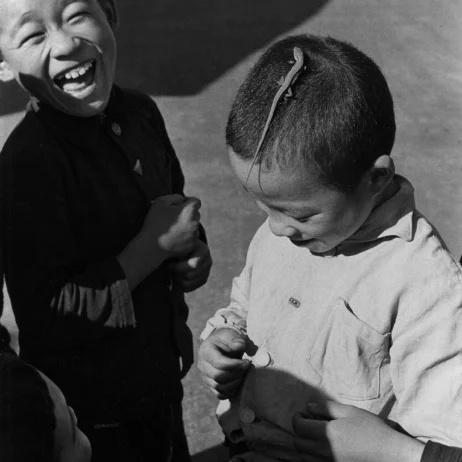

indThis marked the gradual flowering of what came to be known as the “realism” movement in Japanese photography. Domon laid out an explicit series of theses, calling for “the absolute snapshot, absolutely unposed,” and “a direct connection between camera and subject.” Photographers all over the country responded to his call. Among those who were inspired by Domon and later went on to achieve prominence as photographers were major names like Kijima Takashi, Tōmatsu Shōmei (1930–2012), and Kawada Kikuji.